By Chris Stroupe

Tick-borne illnesses being a medical topic, a disclaimer: nothing in this article is medical advice. The references for the article are reliable scientific and medical sources, and I’ve used numbered citations in the text to make it easier to look up detailed information. Nevertheless, consult a medical professional for diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition.

Preventing tick bites

Ticks are parasitic arachnids that feed on blood; they spread disease by feeding consecutively on multiple hosts (1). Tick-borne illnesses can be extremely serious, as described below, and many are difficult or impossible to treat. Furthermore, many tick-borne illnesses take days or weeks to manifest, which can make their diagnosis and treatment even more challenging. All this is to say, preventing tick bites is by far the best way to avoid tick-borne conditions.

Take precautions whenever you’ll be in environments where ticks are common: forest borders, tall grasses, and places with lots of leaf litter. In general, ticks prefer moist habitats (2-4). If possible, walk on the middle of trails and don’t let vegetation touch you. Ticks are wingless, so they wait for their prey to come close to them – a behavior known as “questing” (2).

Prevent tick bites by covering your skin: wear socks, closed shoes, long pants and sleeves, and a hat. Tuck pants into socks and shirts into pants. Ticks are more attracted to light-colored clothing (4-6).

Treating clothes with permethrin, an insecticide that also kills ticks, can increase protection. Permethrin sprays are widely available. Follow the directions on the label, and the treatment will last for about 6 trips through a washing machine. You can also send clothes to a professional permethrin treatment service; such treatments will last much longer. Permethrin-impregnated clothes can also be purchased. Don’t treat skin with permethrin, only clothing (4,6,7). Also note that permethrin is highly toxic to bees, so don’t let the spray drift towards flowering plants, and spray in the evening, when bees and other pollinators are less active (8).

The insect repellant DEET also repels ticks. Apply DEET only to exposed skin – if clothing has DEET on it, it can drive ticks towards the skin (9)! The American Academy of Pediatrics says that DEET is child-safe, but recommends using products with less than 30% DEET on children (10).

If you are bitten by a tick

Check often for ticks when you’re in a place where ticks are likely to be found, and again after you’ve come inside. Ticks can attach themselves anywhere from head to toe. In particular, ticks are attracted to warm, moist areas like behind the knees and ears. Also be sure to check under tight-fitting clothing like socks (6,11).

If you do find a tick that has attached itself, remove it as soon as you can. Using tweezers or a specialized tick removal tool, grasp the tick as close as possible to the skin. Then pull firmly and steadily away from the skin to remove the whole tick without breaking off its mouthparts. It might take several seconds of pulling for the tick to release. Don’t grab the body of the tick. Clean the bite with alcohol or soap and hot water. Save the tick for identification, or take a picture (4,12,13).

Some tick removal methods that aren’t recommended: burning the tick with a match or lighter, or smothering it with alcohol, nail polish, or petroleum jelly. These aren’t effective, can damage the skin, and in fact can prolong the length of time the tick is attached (14).

If you find a tick on you – attached or not – you might want to complete the Virginia Department of Health’s tick survey and send the tick to their lab in Richmond. Note that the VDH won’t test ticks for diseases.

Ticks that commonly bite people in Virginia

- American dog tick (15,16) Adults are about ¼” long, brown with white markings on their backs. In females – which are the main disease vectors – the markings are right behind the head; in males, the white pattern covers the whole body. Spread Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Tularemia, Rickettsia parkeri, and tick paralysis.

- Blacklegged/deer tick (15,17) The main vector for Lyme Disease. Nymphs are mostly responsible for spreading Lyme; they’re tiny, about 1/16” long, and black. Adults are larger; males are all black and females have a red-brown body behind a black head. Preventative treatments for Lyme Disease might be appropriate; contact your doctor if you’re bitten by a blacklegged/deer tick, especially if it was attached for more than 36 hours (18).

- Gulf Coast tick (15,19) Similar in appearance to American dog ticks. Mainly they spread R. parkeri.

- Lone Star tick (15,20) Reddish-brown; females have a white spot on their backs. Adults are about 3/16” long. Transmit red meat/alpha-gal allergy, Ehrlichiosis, Heartland virus, R. parkeri, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Southern Tick Associated Rash Illness, and Tularemia.

- Asian longhorned tick (15,21) As the name suggests, an imported tick that, in Asia, carries many diseases. Asian longhorned ticks are active in Virginia, but it’s not clear yet if they’re spreading disease. Adults are solid brown and about ¼” long.

Tick-borne illnesses

These are serious conditions. If you’ve been bitten by a tick and begin to feel ill, consult a medical professional.

- Acquired red meat/alpha-gal allergy (4,22) An allergic reaction to mammalian meat, e.g. beef, pork, lamb, and venison, that is triggered by the bite of Lone Star ticks. Unlike many food allergies, the symptoms appear several hours after eating meat. Symptoms include rash, itchiness, facial swelling, and potentially life-threatening anaphylaxis, i.e. swelling that closes the airway.

- Anaplasmosis and Ehrlichiosis (4,23,24) Symptoms begin 7-14 days after being bitten: fever and one or more of the following: chills, severe headache, muscle pain, nausea and vomiting, rash, and confusion.

- Babesiosis (4,25) A parasitic disease that usually begins several weeks after a bite from a black-legged/deer tick, but can appear as soon as one week post-bite. Symptoms include fever, chills, muscle pains, joint pain, fatigue and jaundice, and in severe cases, anemia.

- Borrelia miyamotoi (4,26) Also spread by the blacklegged/deer tick. Symptoms include fever, chills, headaches, nausea, body aches, joint pain, fatigue, and sepsis. The fever may cycle up and down every 2-4 days.

- Heartland virus (4,27) Spread by Lone Star ticks. Symptoms include fever, fatigue, headache, and nausea, low platelet and white blood cell counts, and elevated liver function tests. The symptoms can be severe or even life-threatening in immune-compromised or elderly patients.

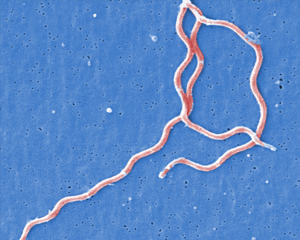

Electron micrograph of spiral-shaped cells of Borellia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme Disease. (Image: CDC) - Lyme disease (4,28) Spread by blacklegged/deer ticks, this is the most common tick-borne disease in Virginia. The initial sign of Lyme is a distinctive rash around the bite. The rash can be anywhere from 1 to 12 inches in diameter, sometimes larger. The rash may be solid red, or have a bullseye appearance. Usually the rash won’t itch or hurt, so you might miss it if it’s in a hard to see place. Later symptoms include fever, headaches, joint or muscle aches, swollen lymph nodes (“glands”), and fatigue.

- Powassan virus (4,29) Spread by the blacklegged/deer tick, symptoms include fever, headaches, body aches, and vomiting, and in some cases neurological symptoms from encephalitis or meningitis.

- Southern Tick Associated Rash Illness (STARI) (4,30) A rash following the bite of a Lone Star tick, sometimes accompanied by short-term fever, headache, fatigue, and muscle or joint pain. The rash and other symptoms can resemble those of Lyme Disease, highlighting the importance of tick identification.

- Rickettsia parkeri (4,31) Spread by Lone Star ticks and adult Gulf Coast ticks, the main symptom is a rash of red spots that can cover the whole body. Other symptoms include fever, headache, and body aches.

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever (4,32) This is a very serious condition characterized by a sudden-onset fever 2-14 days after a bite from an American dog tick or Lone Star tick. Other symptoms include headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and a red spotted rash. The VDH emphasizes that RMSF is a very serious disease and that treatment needs to begin quickly.

- Tularemia (4,33) This bacterial disease is most commonly spread by ticks, but can also be transmitted by inhalation or consuming contaminated food or water. Symptoms of the tick-borne form include an ulcer at the bite site, swollen lymph nodes near the bite, and a high fever (up to 104℉). The VDH also cautions that tularemia is extremely serious if not treated.

Closing thoughts

Awareness, not anxiety, is the goal of this article. That said, gardeners and others who spend a lot of time outdoors should take tick-borne diseases very seriously. The most important messages of the article are that tick bites can be prevented, and that you should check yourself – plus pets and kids – thoroughly for ticks whenever you’ve been in a place where ticks are likely to find you. Knowing that you’ve been bitten by a tick, and being able to identify it, are critical facts that will help medical professionals to diagnose and treat tick-borne illnesses.

References and further reading

- Virginia Cooperative Extension Tick-borne diseases in Virginia

- University of Maine Tick biology and ecology

- Prince William County, Virginia Ticks and tick-borne diseases in Prince William County (PDF)

- Virginia Department of Health Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases in Virginia (PDF)

- Harvard University Lyme Wellness Initiative Dress for tick safety

- Virginia Department of Health Tick prevention

- Harvard University Lyme Wellness Initiative Tick-proof your clothing

- Cornell Cooperative Extension Protect pollinators from pesticides

- University of Rhode Island Protect yourself

- American Academy of Pediatrics Insect Repellants

- Harvard University Lyme Wellness Initiative When you go indoors

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention After a tick bite

- Virginia Department of Health Tick removal

- Childrens’ Hospital of Philadelphia Removing ticks do’s and don’ts

- Virginia Department of Health Tick identification

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. American dog tick

- — Blacklegged tick

- Harvard University Lyme Wellness Initiative Do I need preventive antibiotics for Lyme disease?

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Gulf Coast tick

- — Lone Star tick

- — Asian longhorned tick

- — About Alpha-gal syndrome

- — Anaplasmosis

- — Ehrlichiosis

- — Babesiosis

- — Hard tick relapsing fever

- — Heartland virus

- — Lyme Disease

- — Powassan virus

- — Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness

- — Other Spotted Fever Rickettsioses

- — Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF)

- — Tularemia

Featured image (cropped): Jimmy Liao